The Coach and I

Terry Anne Scott, Ph.D., assistant professor of American history, shares her firsthand relationship with NBA legend Lenny Wilkens.

The cannabis market is growing—fast. At a time when there is more public support for marijuana law reform than ever before, Susan Audino '85 tells us how she found herself at the forefront of standardized testing for the industry and why regulation is so important.

College is seen as a place of discovery; both of the self and the wider world. It’s an opportunity to explore new subjects, interests and world views, and find what will spark passion in your career for years to come.

This was certainly the case for Susan Audino, a chemist on the forefront of lab quality assurance and standardized test methods for the cannabis industry, who explored several different areas of interest before deciding to become a chemist. Audino earned two bachelor’s degrees from Hood, the first in psychology in 1985 and a second in chemistry in 1999, and later went on to earn advanced degrees in both fields.

She credits her enthusiasm in chemistry solely to the chemistry department at Hood—an unexpected interest that would lead her down an exciting path to make her mark on a turbulent and upcoming industry.

“The single most influential factor for my interest in chemistry was the way in which [Hood professors] taught the material,” said Audino, referring to the integrated lecture and laboratory curriculum.

Originally from Rhode Island, Audino found her way to Hood College after visiting a college fair in which Hood had participated. She intended to travel west for college, while her family insisted she stay closer to home. Fortunately, they were able to compromise once Audino landed on Hood.

“I had a very specific list of requirements that needed to be met,” recalls Audino. “It had to be in the country, but close enough to a city. It had to offer science and math. It had to be small, and the classes must be taught by the professors—not by teaching assistants. And, it had to have horses and a stable, which Hood had at the time.”

Hood was able to check off each one of her requirements, so she decided to tour the campus during an admission event. The campus, faculty and students impressed her, so Audino decided Hood was the school for her.

“Best decision I ever made.”

After Audino earned her degree in psychology, she decided to change career paths after developing an interest in law. She took the LSAT and applied to schools, but quickly had another change of heart, and decided to become a chiropractor instead.

Audino was accepted into chiropractic school, and would have to complete a number of courses in chemistry and physics to fulfill the curriculum. Knowing that the classes would be a challenge, she wanted to complete them first.

“I knew that these classes would make me suffer, and I wanted to make the suffering short term,” said Audino. “So, I went to Hood and asked for permission to take them all at one time. I knew that only my alma mater would let me do it.”

She completed two years of classes in just two semesters.

During her second semester, she realized how fascinating chemistry truly was. Originally dreading the coursework, she enjoyed the classes so much that she deferred her admission to chiropractic school to take more chemistry courses. An emergency surgery that semester delayed her admission even longer, pushing chiropractic school off to the next year, giving her the opportunity to take even more chemistry classes, and eventually go on to earn a bachelor’s degree in the subject.

The following summer, Audino applied for and was awarded an independent research grant, which allowed her to work with her undergraduate adviser and the director of forensic chemistry at the Secret Service.

“No one was more surprised than me. I worked on some really cool chemistry over the summer, and by the middle of the summer, I realized I needed to be a chemist—to heck with chiropractic school!”

She began applying to graduate schools to continue pursuing her newfound interest, and went on to earn a doctorate in chemistry from American University. During her coursework, she completed a chemometric fellowship that included chemistry and statistics courses, and conducted independent research at the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

From there, Audino went on to work in laboratories, and a few years later, began auditing chemical and biological laboratories for A2LA, an international accreditation body located in Frederick. She also started her own private consulting company, S.A. Audino & Associates.

In 2009, Audino was approached by a friend in Rhode Island who was opening a cannabis dispensary. With her background as a psychologist for 12 years, and her advanced degrees in chemistry and statistics, Audino was a great prospect to run the dispensary’s quality lab. At first, she was very much opposed to the idea.

“My first response was, ‘Are you crazy? That stuff needs to be illegal.’ I was not supportive of it, but through my friend’s encouragement, I took some time to do the research and I eventually became completely infatuated with the chemistry of cannabis,” Audino said. Through her research, she quickly began to realize the significance of the controversial plant, the industry and the application of her expertise to the field.

Audino’s goal for the industry is twofold: first, for the scientific community to establish standard test methods to ensure consistency and quality of measurements, and second, for regulatory bodies to require testing by quality-driven laboratories.

She began speaking to leadership at A2LA, the accreditation body for which she worked, helping identify the need to assess and provide direction for cannabis testing labs in order to accredit them to international laboratory quality standards. At first, like her own response, she was met with hesitation, but they too realized the industry was quickly growing. She began working with them to research and identify the necessary resources they would need to meet customer needs.

Audino also approached AOAC International, an organization that develops standard test methods, primarily for the food (human, pet food, animal feed) industry. She formed an advisory panel for the organization, which consists of committees that work to develop test methods specifically for cannabis. Audino has given lectures, been a frequent guest on webinars, and traveled the world to attend conferences advocating for standard test methods in the cannabis industry. She is now a recognized expert all over the world. This work catapulted her into serving as a technical adviser and resource to several government and state agencies that are developing cannabis programs.

With many industries in the U.S., there are federal regulatory bodies that enforce standard test methods to ensure consumer safety. Organizations like the Food and Drug Administration and the Consumer Product Safety Commission exist to protect consumers.

For example, the Department of Agriculture will routinely pull products from the shelves of grocery stores and test them to ensure their contents match their labels. Manufactures are held accountable for the safety of their products, and consumers are accurately informed about the products they are purchasing.

However, since cannabis is still federally illegal in the U.S., there is no federal body to provide standard, regulatory oversight. Regulatory provisions are left to each state, creating an environment with 30 independent operating systems, all with their own standards and margins of error. By using many different test methods, laboratories can generate many different results.

“Their results could all be correct, or all be wrong, but there’s no way to attest to that,” said Audino. “Laboratories need to be able to follow standardized test methods and know the levels of uncertainty, so that products can be manufactured with good laboratory practices and be tested accurately by third-party laboratories.”

If you look at the label on a food product, it lists the percentage of components such as protein, sugar, fats and sodium. Likewise, in the cannabis industry, manufacturers must be transparent in the components of their product, such as THC, THCA and CBD. Different chemical varieties or “chemovars” of the plant contain different concentrations of various components, and consumers have the right to know what they’re purchasing. Testing labs attest to what’s in the product, including adulterants such as sand, hairspray, insect remnants, and mold or mildew.

Several challenges face Audino and others who fight for standardized test methods for cannabis. First, these organizations must work around different state laws to conduct testing. Because it is illegal for cannabis to cross state lines in the U.S., it’s impossible to test products from different states at one time.

Second, additional test methods must be developed for foods that contain cannabis, as opposed to the traditional flower that most people think of when they hear the word cannabis. These foods are becoming increasingly popular, but pose a higher risk to consumers because of rates of absorption in the body.

“There’s a lack of education about eating cannabis, as opposed to inhaling it,” said Audino. “A chocolate bar may be labeled as containing 10 milligrams of THC, but does it really have that much in it? Is that 10 mg distributed evenly throughout the food? Does each segment really contain one mg each? This is important because it can severely influence the dose a person may consume, and could potentially make someone sick if they take a different dose than intended.”

Now, Audino wears many hats each day. She serves as an adviser and team member for a large number of private and government organizations whose mission it is to create standard test methods for cannabis. She also owns and operates her own consulting company, writes articles and papers on the subject and is a guest author and editor for several publications, among other roles. She also works in a number of other industries, including analyzing jet fuel and food products, and serves on Hood’s Board of Associates. Audino also has ongoing business plans in place, which she expects will quickly solve some major challenges in the cannabis industry.

As for the future of the cannabis industry, Audino says “no one really knows” what will happen, but one thing seems certain—the U.S. may follow Canada’s lead and lift the federal prohibition. And, when that time comes, Audino hopes that standardized test methods will hold cultivators and product manufacturers accountable and accurately inform consumers of the products they’re purchasing. ■

Wallis Shamieh ’15 is a freelance writer and marketer based in Jefferson, Maryland.

Terry Anne Scott, Ph.D., assistant professor of American history, shares her firsthand relationship with NBA legend Lenny Wilkens.

At Hood, April Boulton, Ph.D., an insect ecologist by training, has been examining some of the factors responsible for declining bees. She was instrumental in the 2016 passage of the Maryland Pollinator Protection Act, which made Maryland the first state to ban residential use of a pesticide class. Get the facts and see how you can help.

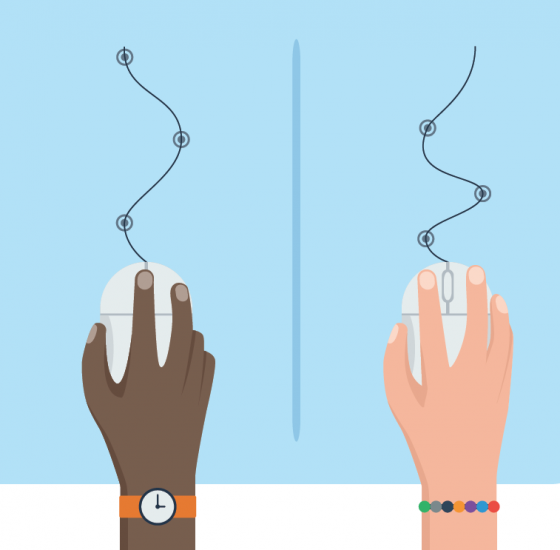

Like a fingerprint, unique mouse movements could protect your personal information. Kamal Rangavajhula, a Master of Science in Management Information Systems (MIS) candidate, conducted research using behavioral biometrics.

Information will vary based on program level. Select a path to find the information you're looking for!